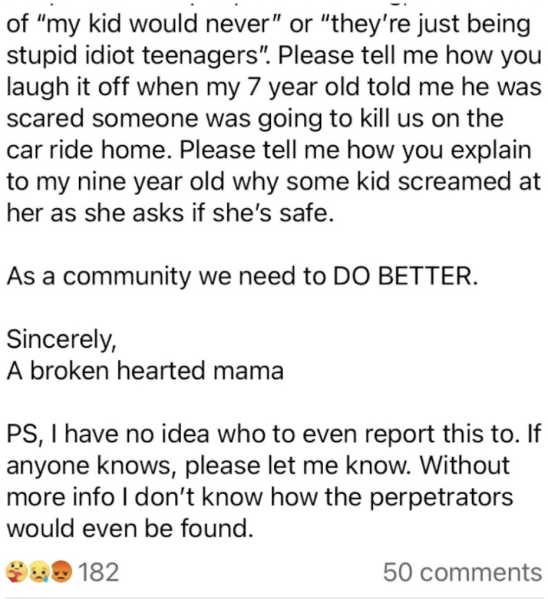

On October 13, 2023, a white woman and her mixed 4-, 7- and 9-year-old children were leaving the Friday night SRV football game when a group of teenagers in an SUV, later confirmed as San Ramon Valley High School students, shouted a racist slur directly to their faces as they passed by. The mother ushered her children into their car, fleeing the scene confused and scared.

Later that night, the 7-year-old asked his mother if he was going to die, and the 9-year-old expressed deep concern over the safety of her siblings. These children, not even old enough to attend middle school, experienced a targeted attack on their identity, the first and by no means the last instance of racist hate these budding humans will face.

Puzzled, angry, and hurt, the mother took to social media, recounting the experience on the “Parents of the SRVUSD” Facebook page and calling for reform from our school, emphatically declaring, “we need to do better.” Without knowing the identity of the perpetrators, though, our options are painfully limited; at best, lectures about how unacceptable racism is do little more than instill anonymous guilt without any tangible punishment.

The October 13 incident is just the latest instance of racism at this campus, and it will in all likelihood not be the last. It is difficult, however, to envision effective countermeasures when such prejudice is seemingly molded into our culture, as well as our very way of living.

This inability to deliver just retribution stretches well beyond this incident and our campus as a whole; the lack of response from the faculty, district, and broader community in the following weeks mirrors the callousness and apathy that undermines every effort to cultivate any sense of moral fairness in not only our community, but our entire world. So, how are local, legal, and universal systems flawed and corrupt, and what can we do about it?

Injustice festers in the entire world, only exacerbated by the implicit racial disparity within our social and legal structure; prejudice infects every niche of our authoritative system, from the law enforcement that detains “wrongdoers” to the courts that try them.

You are likely familiar with the murder of the defenseless George Floyd and the national outrage it sparked against police brutality and systemic racism. It is incredibly important, however, to recognize that there have been many George Floyd’s throughout history, and still reform has not occurred; it seems like every few decades, targeted police brutality against minorities inspires a raging movement against racism in law, and then the spark fades just as quickly as it began, until another incident is brought to the public eye.

Before George Floyd in 2020, it was Eric Garner in 2014, who was tackled and strangled by a police officer despite being unarmed and pleading for air; before that, it was Oscar Grant in 2009, who was shot and killed by a police officer in Oakland while unarmed and lying on his stomach; before that, it was Rodney King in 1991, who was nearly beaten to death by four officers who were all acquitted of charges; before that, it was Emmett Till in 1955, who was tortured, mutilated, lynched, and thrown into a river at 14 for looking at a white woman wrong. Till’s assailants were also cleared of all charges, and because of the double jeopardy clause of the Fifth Amendment, could not be tried again, even after publicly boasting about their deed years after the trial.

There are also, of course, the horrifying statistics of California’s prison population, which counted 549 people in prison per 100,000 residents as of 2021, more than four times as many as China’s 119 and just shy of twice as much as Russia’s 300. While this is an undeniably eerie statistic in and of itself, it becomes downright chilling when considering just how many of these convictions are incorrect, founded on bias and little else.

For example, Bryan Stevenson’s book Just Mercy recounts the story of Walter McMillian, who was unjustly put on trial for murder, abused in the system, knowingly kept as a scapegoat by the police department, and nearly put in the electric chair despite his airtight alibi. Even following his acquittal in 1993, though, McMillian remained haunted by the trauma he endured on death row, which manifested in long-term health problems, including dementia, that followed him to his grave. He had concrete evidence he was not at the scene of the crime, corroborated by multiple witnesses, and yet he was selected and groomed by the police and Alabama courts to take the blame simply because he was African American. There is no telling how many more Walter McMillians are out there today, and there will continue to be Walter McMillians so long as society fails to reform and continues to place their faith in a justice system with unjust roots.

Another part of the problem is also the apathy of the general population; many citizens purposefully ignore or even embolden the courts’ wrongful convictions when granted power over a court case in the form of jury duty.

“I would say maybe one in ten jurors actually go in saying ‘this guy’s innocent until they prove him guilty,’” says SRV psychology instructor and former Alameda County public defender Paul Horvath in an interview. “I would say nine in ten go in [thinking], ‘he’s guilty until he’s proven innocent’ because their assumption is: if he’s been arrested, if he’s been charged, if he’s in the courtroom, he’s guilty.”

The implicit prejudice we have against the incarcerated, even without concrete evidence, contributes to rulings that are less informed and no less extreme than if there was sufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt. In Just Mercy, for instance, Walter McMillian was placed on death row for six years and scheduled to be executed for a crime he did not commit before Stevenson had his case overturned; a closer look at the evidence opposing McMillian revealed most of it to be botched or even coerced by the Alabama police, with the sole intention of placing McMillian in prison. In other words, if not for a reevaluation of the trial, an innocent man would have been killed, not because there was strong enough evidence opposing him, but because the law itself worked against him to ensure there was not strong enough evidence supporting him. If we are to assume that the same philosophy, the notion of “guilty until proven innocent” in conjunction with the authoritative system’s own mistakes and prejudices, is still being exercised in courts today, can we really claim our systems and the punishments they dole out are just, fair, and unaffected by preconceived biases?

Between the police, the prison, and the courts, bias and prejudice reside in every nook and cranny of the administration we call just; these problems are implicit, they are grave, and they are permanent fixtures to our law, because the systems designed to implement justice and fairness are flawed and corrupt themselves.

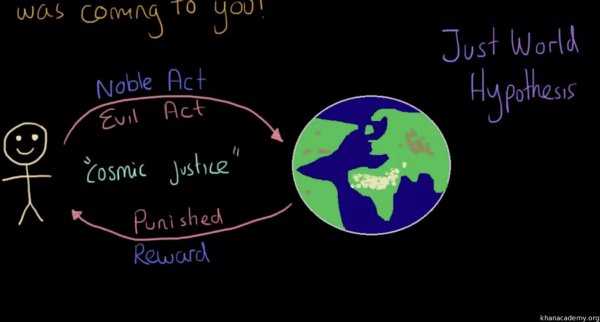

The corruption running rampant through the system is no secret, yet many remain resolute in their belief that justice will be served, if not through the law than through the universe itself. In psychology, this is called the just world theory, the popular notion that the world is inherently just and fair; people will get what they deserve, and they will deserve what they get.

People often subscribe to the just world theory unconsciously, largely because the existence of a divine order or karmic fate offers a sense of consistency and predictability that is incredibly soothing to human nature.

“The human brain is designed to see patterns and to see cause and effect, and so superstitions develop because we did one thing and then something happened afterwards and we make the connection,” Horvath explains. “If it’s really that a lot of things are just random, and there’s no real cause and effect, I think that’s very disconcerting because then that means there’s no way of telling if there’s going to be an earthquake or a tsunami or a car accident or COVID or whatever and that’s a very scary world, and so I think it’s more comforting to think, ‘as long as I don’t do terrible things, terrible things aren’t going to happen to me.’ And I think that’s comforting to people.”

Because of their faith in the just world theory, the typical citizen makes little to no effort to correct the injustice they see because they believe the natural order is such that good will bless the deserving and evil will befall the undeserving. Horvath ties this concept back into the justice system, hypothesizing that “it’s too upsetting to think about innocent people getting convicted or that the system isn’t fair or that it’s prejudiced; that is just so upsetting and so it’s hard to go about your normal life if you realize that … I think it’s easier to live your life to think that the world is fair, and that good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people and you don’t have to worry about it.”

The cognitive friction created when one recognizes the magnitude of the corruption within the systems they trust and invest in is so great that reconciliation with oneself and one’s morals becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible; thus, it is much easier to believe that karma will reward and punish people fairly, automatically, and autonomously, regardless of human intervention.

But justice is not implicit, and there is no scientific evidence to indicate that “karma” actually exists; people only choose to believe in supernatural retribution because the alternative is to recognize the world as inconsistent, unreliable, apathetic, spontaneous, and chaotic. To deny the just world theory is to admit to oneself that equality and balance are not the natural state of things, that not everyone is rightly punished for their sins or fairly rewarded for their virtues, that there is no such thing as paranormal influence or karma, and that what you do and who you are does not ultimately matter to the universe.

People like what they can predict, and they like what makes intuitive sense; given the choice between fair and equal consequence and unpredictable and spontaneous disorder, they will choose the former every time, despite all evidence to the contrary, because that is what allows them to maintain the illusion of cohesive and meaningful life. The harsh truth, in short, is that there is no power up above that will magically make things right; as a species, we are, for all practical intents and purposes, alone in our quest for justice.

So, if nothing we do matters, what is the point of this article? Am I just writing to inform you that nothing matters, that karma is not real, that justice is an impossible standard to uphold? Partly, yes; in order to change your viewpoint and influence your actions, it is necessary to overhaul your fundamental beliefs. The purpose of this article is to inspire you to take charge, to be proactive, to empower you with the knowledge that what you do as an individual matters. Things in the world are not going to get better under the rule of a historically and implicitly corrupt system, and you cannot rely on some greater supernatural power to deliver just and fair retribution on its own. By ignoring the problem, by expecting someone or something else to take charge, you actively perpetuate the cycle of injustice within your community and, to some extent, the entire world.

I am not endorsing drastic action. Your choices do not need to be exaggerated or flamboyant to be impactful; the most effective way to influence and improve your world is through integrity and subtlety, not theatricality. All it takes is the courage to act, even if such action transpires in anonymity. You are an individual, and thus you have agency, the ability to make meaningful decisions even in the face of resistance; you can stand up against the corruption around you, and you can become the harbinger of just retribution.

The vast majority of injustice occurs due to a bloated sense of pride and safety, because those who commit acts of bigotry and hate often evade repercussions. This can be seen on small scales, such as in our own community with an instance of drive-by racism, and on large scales, such as in a courtroom where an entire police system set up Walter McMillian as a scapegoat and channeled the very corruption it claims to fight.

While these two cases may seem entirely dissimilar in cause, they share roots in simple acts of bigotry and hate, something you can combat right here on campus. If you know anyone who manipulates, demeans, harasses, bullies, or even abuses others, take a stand against them; tell them as their peer that what they are doing is fundamentally wrong and will not be tolerated, at least by you. They may just crumble at the mere prospect of retribution; without the complete assurance of an ego boost, along with the threat of social consequence. All it takes is a simple callout to prevent injustice from incubating within someone and festering within their environment.

Many forms of injustice are grounded in historical ignorance; by educating yourself and those around you on the implicit bias within our system and what it looks like in practice, you can serve as a voice of reason to those who are perpetuating the cycle of injustice and recognize when you yourself are crossing the line. Take the time today to learn something practical; research the history of slavery, racism, and bias in California, in the United States, and in the world. Next time you hear your peers dehumanizing someone with a remark or minimizing a culture with a snide joke, be informed enough to confront them with confidence and tell them exactly why what they said was wrong.

San Ramon Valley High knows the significance of reform through education well; just two months ago, we held the first culture fair at our school, in which students of all ethnicities and backgrounds gathered to share samples of their diversity.

“There’s a lot of more subtle racism at our school than there is the blatant kind, ‘microaggressions’ born of ignorance,” club fair contributor, Hispanic Student Union co-president, and Black Student Union member Damian Gibson writes via iMessage. “That’s the kind of racism the culture fair wanted to address, by exposing all of the different cultures at our school that are typically snubbed and targeted and instead making them something to celebrate. I think it succeeded in that; it gave many people the ability to share in the lives of people they normally wouldn’t care to.”

Approximately 500 students, a quarter of the entire student population here at SRV, visited the club fair at some point during the lunch period it was running for, and while the free food was undoubtedly a large draw, hundreds of students devoted time to learn just a little more about the world outside of Danville.

Events such as the culture fair play a major role in educating the masses and introducing newer cultures into society; by encouraging, endorsing, and attending these events, we can combat injustice by finding familiarity with what was once alien to us, and, ideally, defeating our preconceived biases by educating ourselves and recognizing each other’s humanity.

As an individual, you have the power to educate others with your voice, and broadcast your voice to the world. Your voice is still singular, however, and therefore can be hard to hear amid thousands, if not millions, of others; a symphony of voices in unison, on the other hand, holds much more power. Assemble a group of like-minded individuals, or join an organization that stands in opposition to injustice.

Our own campus has multiple clubs standing against injustice and oppression, especially in regards to ethnic diversity, all of which are welcoming and free to join; these include the Asian Student Union, Black Student Union, Hispanic Student Union, and Jewish Student Union.

Many of these clubs have also gone the extra mile in establishing communication between clubs to provide all members with a comprehensive understanding of a multitude of cultures. “This year our school’s student unions have taken the unprecedented step of working together to make things like the culture fair happen,” Gibson declares, “as well as many things behind the scenes many people may not know about, such as inter-club meetings to teach each other about our traditions and culture. This isn’t something we’ve done because the adults at our school pressured us to … It’s a demonstration of what you can do by joining a Union and using your collective power to make a change how you want to see it happen.”

If you would like to find people you identify with or just learn more about the cultural backgrounds of your peers, seek out some of these clubs.

You can give back using your resources, too; investing in the right organizations can provide good people with the means to do great things. The aforementioned Bryan Stevenson, for example, is the head of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit that, according to its website, “provides legal representation to people who have been illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced, or abused in state jails or prisons.” By donating online to their initiative, you could potentially save a life from death row, provide protection for victims trapped in the system, or aid in rehabilitating and reintegrating the acquitted into society after they are released from prison.

One of the best ways to combat systemic injustice in our courts is to simply perform our civic duties; if people stopped avoiding jury duty, there would be less of an opportunity for misinformation and misunderstanding to undermine or sabotage rulings. Wrongful convictions are made due in no small part to the jury being composed only of the infinitesimal demographic of people who actually show up; many citizens with the potential to offer valuable insight, wisdom that could potentially change the entire course of the case, choose instead to shirk their responsibilities, and inadvertently damage the integrity of the verdict as a result.

This remains true among our local jury duty candidates, who seldom appear in court when summoned. A study posted on SFGate in 2015, for instance, surveyed 14 of the largest counties in California, finding that about 23% of residents called upon for jury duty do not actually participate, if they respond to the summons at all. In practice, this means that one in every four or five California residents summoned to jury duty never actually appear in court, which is a considerable chunk of perspectives that is quite simply wasted, discarded as if they were nothing.

Horvath cites this gross ignorance of one’s civic duties as a major suspect for wrongful convictions, specifically challenging younger candidates’ reluctance to give the justice system the time of day. “I think someone in their 20s could have a much better grasp of what could’ve actually happened with the crime than someone in their 70s that has no clue about drugs or culture today or cellphones or anything and they’re just going to go ‘guilty’ when they don’t really know,” Horvath theorizes; he encourages any and all citizens who receive jury duty summons to respond with earnest and sincerity, emphatically declaring, “Serving on a jury is an important task, and we need your wisdom and knowledge to be there.”

All it takes to reinstill legal power with honesty and integrity is showing up to jury duty when you are summoned; taking your designated seat among the jury prevents the possibility of that seat being supplemented by someone who has a fundamentally different understanding of the world than you do, when your insight may very well decide the verdict. By answering the call to action, you make a substantial difference in the outcome of a given case; even if it is not fun, even if it is, dare I say, boring, affecting the system in a positive manner by changing the courts for the better is worth the time commitment.

Horvath also believes the system is already headed in the right direction because it has begun recognizing and respecting its defendants’ humanity, citing the difference in how the law handles drug cases today compared to 30 years ago as the epitome of that growth.

“At the time when I was a public defender,” he remembers, “it was just all about harsher sentences for dope fiends, and [we were taught to] just put them behind bars longer and longer and that they were scum of the earth, and now the attitude is more that, ‘maybe this is a health crisis; it’s not just criminal justice but maybe we should figure out some way to get these people off the drugs and figure out a way that we can make them a part of society… they’re still a person; they’re not a scumbag just because they’re addicted to oxycontin.’”

This shift in perspective marks a monumental step forward for the justice system; the law no longer attributes one’s decisions entirely to their disposition, but now allows circumstance to play a role, escaping a psychological trap called the fundamental attribution error. The recognition that the choices we make are at times beyond our control introduces greater lenience and empathy into the system, progress that may very well foretell true change.

Injustice is undeniably implicit within the laws of today’s society, and it may very well take decades of reform to see real change. Every movement, every revolution begins with an idea and an effort; once momentum begins building, everything is well and good, but something, someone is required to break that initial inertia. With the will to act, the knowledge to speak, the determination to persist, and a little luck, any singular person has the ability to get the ball rolling. If you truly want to make a difference, you can; as an educated individual, you have the ability to inspire real change among your community, and with your voice in conjunction with others, the world.

Change, however, comes in time; Our school will not be absolved of all injustice in a day, and the justice system will not be overhauled in a night. For now, all you have to do is watch. Look around you; notice the minute interactions; note the apathy; observe how prejudice and injustice have worked their way into the foundation of our culture. Recognize that your world, your systems, and your community are flawed … and then reach out and change it.